Analysis

Hidden in Plain Sight: Issues for Women following the Earthquake

2016-08-30

When reports broke internationally about the magnitude of last year’s earthquake, international media sources and local NGOs were already speculating on how the disaster might come to affect some of the pre-existing social and political issues in Nepal. How would the sudden influx of millions of dollars of aid assistance alter the already unsteady political climate of the country? Would the vulnerabilities left behind by the earthquake result in a growing number of human trafficking cases? One article from The Guardian warned that traffickers may even pose as relief workers to lure vulnerable women and girls into trafficking. This story is reflective of a common narrative following the earthquake- that Nepal would see a spike in reports of abuse against vulnerable communities such as single, widowed, or lower-caste women.

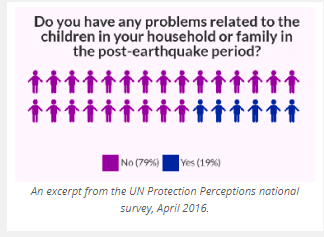

Maiti Nepal, which advocates and protects victims of trafficking, reported little to no increase in reports of human trafficking in Nepal in the year following the earthquake. The Citizen Feedback Surveys conducted by the Inter-Agency Common Feedback Project of the UN also suggested that gender-based violence has only been a peripheral risk for communities affected by the earthquake. In the Protection Perceptions survey for April of 2016, respondents did not even cite safety issues for women or children as a primary concern, hinting that perhaps this wasn’t a risk widely faced by victims. When I asked a representative from the UN survey her thoughts on the news and NGO reports warning of heightened gender-based violence and trafficking following the earthquake, she said she believed that, based on the data they had received, these fears were simply fueled by excessive media coverage.

A Closer Look at GBV Reports: Nuwakot and Dhading

Some data collected at a more local level present a counter-narrative to the narrative of gender-based violence as a minimal problem in earthquake-affected communities. Between July of 2015 and July of 2016, the Womens’ Cell at Bidur, Nuwakot Police Station filed 95 non-criminal gender-based violence cases, the majority of which were classified as domestic violence. Additionally, eight cases of rape, five of attempted rape, and five polygamy cases were also filed. Officer Tamang, director of the Women’s Cell, said these numbers marked an increase since the previous year.

Sharmila Upreti, chairperson for the Nepal Federation of Indigenous Nationalities in Nuwakot reported that of the 77 human rights cases reported to her organization following the earthquake, 48 of these were related to gender-based violence. She felt that the majority of these cases were related to women living in temporary structures and settlements.

The Womens’ Cell at the police station in Dhading Besi presented even more shocking data for the past year. The office received 155 reports of domestic violence, of which only six went to court. Additionally, there were five reports of human trafficking, 31 of rape and 9 nine attempted rape. In May of 2015 alone, the Dhading Besi office received six reports of rape.

Sahayatri Samaj Nepal, an NGO which supports victims of gender based discrimination and violence, filed 474 cases of gender-based violence between July 2015 and 2016. Generally, these types of cases, considered non-criminal, are mediated and settled within the NGO office, thus rarely make it to court, and sometimes not even to the police station in the district headquarters.

–It’s interesting to note that the overwhelming majority of abuses reported to local police or NGOs do not get reported to media sources, thus are not represented in Nepal Monitor’s data.

Data, Perceptions, and Opinions: What does it all mean?

The number of reports and general perceptions in Nuwakot and Dhading challenge some of the national trends for gender-based reports since the earthquake. They also shed light on an important question to keep in mind when assessing victim-based reporting– what does an increase in reports actually mean?

Many community members in Nuwakot and Dhading believed that the spike in reports in their district was a product of the awareness and empowerment campaigns initiated in the past year and a half. These projects were largely targeted at women and young girls residing in temporary displacement camps, and aimed to educate young girls and women to local resources for reporting abuse. Ms. Sapkota, Executive Director of Sahayatri Samaj Nepal in Dhading Besi believed that these projects were so far-reaching in fact, that all of the families in displacement camps, which numbered up to 5,000 in the months directly following the earthquake, were reached by at least one awareness or gender-empowerment campaign.

Legal and Social Limitations to Reporting Gender-Based Violence

While the outreach following the earthquake undoubtedly empowered women to report cases of ongoing abuse, it is important to first take note of some of the legal and social limitations women face in reporting such incidents. According to Nabdeep Shrestha, INSEC District Representative in Bidur, more than 99% of domestic violence charges get settled in a police station or NGO office. This is possible because cases of domestic violence are considered non-criminal cases under the Domestic Violence Act of 2008. This also means that in most cases married women return home with their abusers. Given this fact, it’s clear to see why organizations like Sahayatri Samaj and woman human right defenders believe women avoid reporting abuses for fear of retaliation. On top of this, women often face social exclusion for reporting spousal abuse, getting a divorce, and even for being widowed. When these social and legal risks to reporting are combined with increased vulnerabilities of living in temporary shelters, or an increased economic dependence on spouses, women face great limitations in seeking out the justice they deserve.These limitations make it difficult to equate last year’s spike in gender-based violence cases in Nuwakot and wholly with an increase in empowerment and awareness.

Displacement camps: A Place of Refuge or Heightened Risk?

In addition to structural limitations to reporting abuses, women living in temporary camps after the earthquake faced some of the largest risks for abuse and harassment. People In Need’s ‘Her Safety Assessment’ in Sindhupalchok seem to parallel the conditions in camps in Dhading Besi according to Radhika Sapkota of Sahayatri Samaj Nepal. Many shelters lacked locks or electricity, and women reported cases of harassment by men in the camps. It seems that while livelihood and education projects reached a large number of displaced women, basic securities might have at times been overlooked as structures were hastily created to accommodate as many people as possible. Various community members in both Nuwakot and Dhading also believed that internally displaced people from outside VDCs had trouble integrating into their new communities, and even faced discrimination by locals. When Sahayatri Samaj defended a young girl who reported being raped by a bus driver when traveling to her home VDC, the organization received backlash from community members in Dhading Besi who felt that focus should be placed on primarily supporting over ‘outsiders’.

For more insight on the data and locations of displacement camps in earthquake-affected districts click here for a report by the International Organization for Migration.

The conditions for women in Nuwakot and Dhading since the earthquake present somewhat of a paradox– women, particularly those in displacement camps, were targeted for empowerment and livelihood projects, thus increasing the likelihood that they would report abuse. But specific accounts also shed light on some of the social and legal limitations that discourage women from reporting abuse. These issues make it difficult to exhaustively argue that an increase in reports of gender-based violence at a district level is largely a product of awareness, or even media-based fear incitement. While progress has been made in the reconstruction process, the vulnerabilities bred from last year’s earthquake may continue to play a role in defining conditions for the women in earthquake-affected districts for years to come.

Special thanks to two members of the Nepal Monitor team for their contributions to this blog: Arpana Shrestha, Program Officer, for her translation assistance and Rajya Laxmi Gurung, Training and Outreach Coordinator, who organized interviews with key informants in Kathmandu, Nuwakot, and Dhading.

Haley McCoin and Raheem Chaudhry are AidData Summer Fellows working in Kathmandu with Nepal Monitor this summer. Haley and Raheem are both students at The University of Texas, Austin, where they work for Innovations for Peace and Development, a research organization affiliated with AidData. Haley is pursuing a degree in International Relations and is specializing in Middle East Studies and Arabic. Raheem is pursuing his Masters in Public Affairs and anticipates graduating this August.